Todos los 22 de mayo, año tras año, desde 1993 se celebra el día internacional de la diversidad biológica. Este día fue promulgado por las Naciones Unidas, para visibilizar una de las realidades más importantes y que más impacto tiene en la vida diaria de todos los seres vivos que vivimos en este planeta: la biodiversidad.

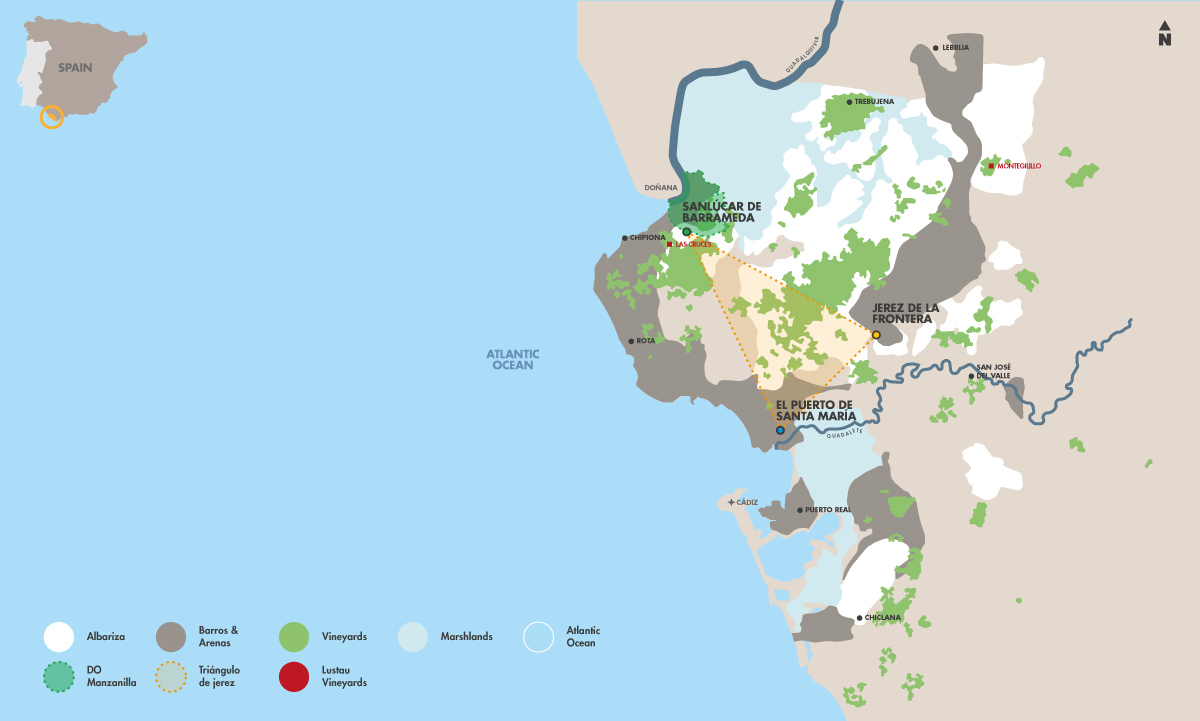

When contemplating the factors mentioned above, as studied in the CSWS® program, the sherry region understandably presents itself as a complex and diverse area. Location, mesoclimates and microclimates, grape varieties, and soils are all great examples of the natural terroir, and the interconnection of these elements gives rise to an extraordinary landscape that forms the basis for these wines’ extraordinary personality.

The meaning of the word “terroir” and its etymology is not coincidental. Although the concept (broadly recognized as French terroir) refers to the conjunction of soils, climate, tradition, and topography, its etymology and literal meaning directly refer to the soil. Yet in Spanish, the translation of this word comes closer to the literal meaning for soil, tierra, “terruño“. Over time, the soil, the land itself, has been a predominant factor in the inception and understanding of wine regions around the world. And once again, Jerez is an inimitable participant of this segment.

Soil from the Marco de Jerez: Albariza

Sherry is known for having a prevailing type of soil in the region: “albariza”. While there are a few other types, (barros y arenas), it’s the first of the three that holds significance not only in terms of presence but also in tradition and history.

Albariza soil (whose name comes from the Latin word “alba,” meaning white) is primarily composed of calcium carbonate, clay, and marine fossils or diatom sediments date back millions of years ago. Andalucía, the southernmost region of Spain, to which the Jerez region belongs, was submerged under the sea around 60 million years ago (Oligocene era). Over time, rock formations and areas of submerged ground gave way to the complete retreat of the sea, creating isolated and shallow lakes. During this process and because of the sea’s dissipation in the area, the soil (known as “barros”) found in these in marshlands close to the Guadalquivir or Guadalete rivers at the lower part of the hills is rich in organic matter. On the other hand, in the higher zones, the fossils of marine organisms (such as diatoms) and algae accumulated on the ancient seabed came out to the “surface” of the land giving birth to our “albariza”, the iconic soil from Marco de Jerez.

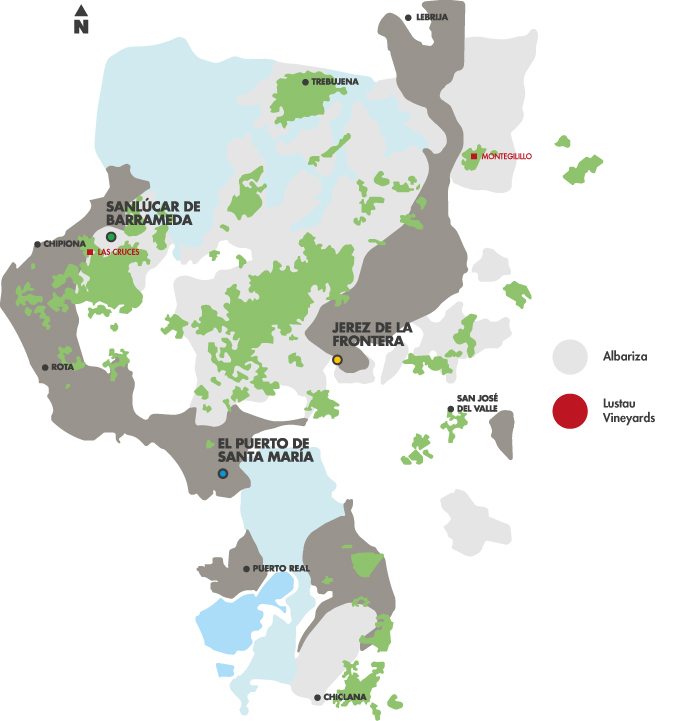

Albariza soil is therefore the most distinctive soil of the Jerez region, found in its higher areas, hills and in inland areas of the sherry wine DO.

Despite the concentration, composition, and location within the geographical boundaries of the region, the soils resulted from mixtures of subtypes of soils where the topography, orientation, time, and former waters caused great diversity in the land, giving each vineyard area (or “pago”) a unique identity. As a result, in the 18th century, the entire area was classified into the so-called “pagos.” Pagos of the Jerez region are vineyard land extensions that, due to their location, mesoclimatic and microclimatic conditions, the close proximity to the sea, and/or soil type, produce grapes with distinct characteristics. This classification also led to the creation of the concept of “Jerez Superior.”

Although the Jerez Regulatory Council no longer maintains the requirement that registered vineyards on Jerez Superior classification must be on albariza soil, this designation formerly required the presence of this type of soil to classify an area as a production zone for very high-quality grapes.

In summary, the presence of albariza in the region is partially responsible for the significant geological, topographical, and climatic diversity that can be found in vineyards. This diversity leads to tremendous wealth for the region.

Where can Albariza be found?

This type of soil is not exclusive to coastal areas or to Jerez. There are other regions within and outside the Iberian Peninsula where remains of marine fossils and diatoms have been found although they are now far from sea or water masses. Champagne is one such example. Just as in Andalucía, this region was uplifted due to the collision of the African and European tectonic plates. This historic and geological phenomenon caused the emergence of mountain ranges like the Alps. This is why it’s possible to observe diatoms and fossil remains at extreme altitudes, such as 1,500 meters above sea level, or distances of over 200 km from the sea.

Discover the factors that unite the regions of Jerez and Champagne, and learn more about the cultural heritage of these two regions here

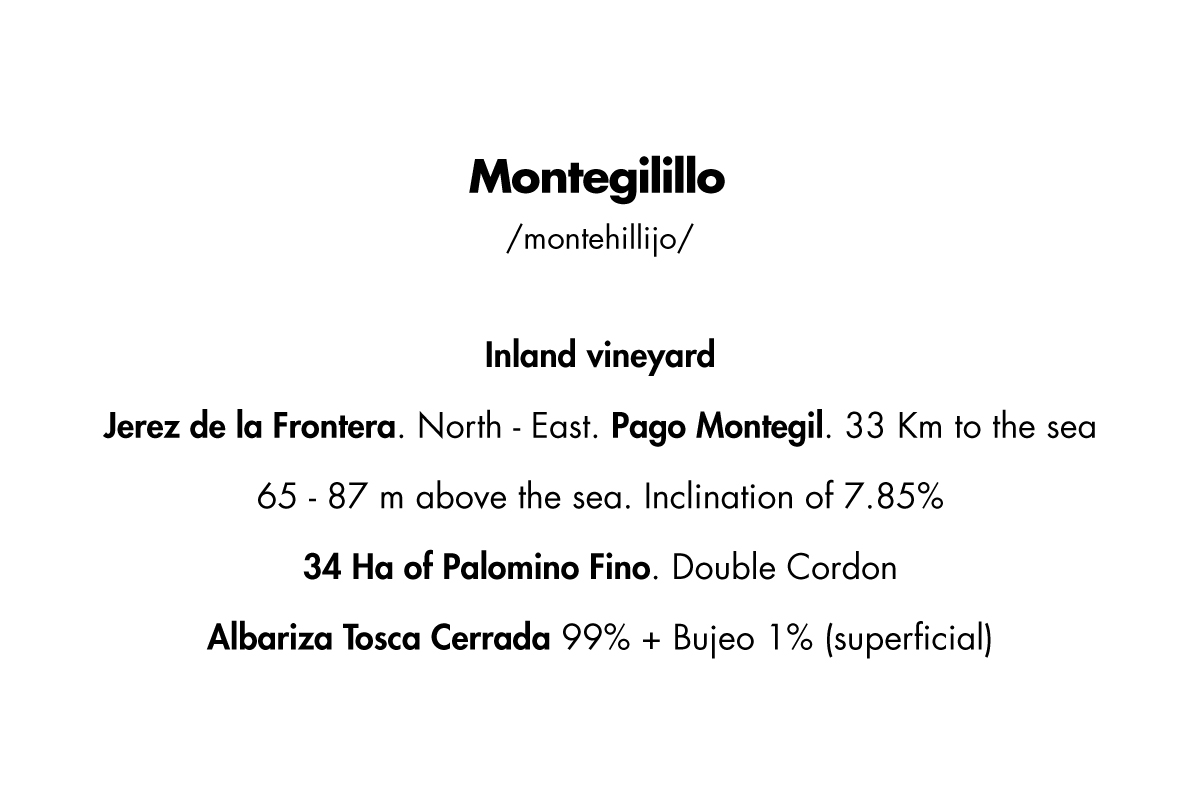

Lustau’s contribution to Jerez Superior: Montegilillo.

Lustau currently owns two vineyards, recognized for being completely differing from each other. Montegilillo and Las Cruces. The first is located inland, and the second one by the coast. These two antithetical concepts complement the diversity and variety of styles and expressions within the Lustau wine collection.

Montegilillo is the perfect example of a characteristic albariza vineyard of Jerez: a moderate elevation, located in the inland area of Jerez de la Frontera (at pago Montegil), with a notably interesting slope and albariza soil comprised of high levels of calcium carbonate. Montegilillo is also ideally located on a hillock with a soil moisture content that’s conducive to the production of very high-quality palomino grapes.

Albarizas, however, can also be found in less concentrated form, mixed with other types of soils, creating highly heterogeneous compositions across the region. This is the case with the Las Cruces vineyard, where, in different proportions and areas, the combination of the three characteristic soils of the region takes place: albariza in the higher parts of the hill, arenas (sands) in the lower areas closer to the Atlantic Ocean, and isolated lots of “barros” (clay).

Albariza Characteristics: what makes this soil so special?

The main characteristic of this soil, and the primary reason why it’s highly valued among growers and wineries, is its water retention ability. This soil can hold moisture collected through water during the rainy season (November – April) and store it in its deepest stratums, providing nourishment to the vine throughout its life cycle. This compensates for the low levels of organic matter the soil has and also supplies necessary nutrients to the vine.

Due to its highly porous structure, water storage occurs in the form of moisture. Albariza soil cannot fully absorb water. This is advantageous for the vine, as there’s no risk of waterlogging or drowning. The soil’s porosity also allows for a continuous and steady airflow, allowing the plants to “breathe.”

Furthermore, Its color causes light reflection. The sunlight waves are repelled, avoiding overheating, and preventing them from being projected towards the vine. Thus, both soil and vine do not struggle during the hottest summer months reflecting light and keeping the roots and plant cool, even in extreme situations like drought or heatwaves.

A divergent soil.

As seen previously, the mixture of soils has led to a great diversity in the vineyard, in the grapes, and hence, in the wines of the region. This medley of soils is far more intricate than it might initially appear. There is a myriad of types and subtypes of albarizas in the region, along with soils that include “albariza” but aren’t classified as such due to its minimum presence in their overall geological composition. The list and breakdown would be extensive and a matter of a thesis. The following section highlights the three most significant types of albariza soil of the region:

– Lentejuelas: The lentejuela albariza has a soft and fluffy composition, with a granulated texture and a high content of diatoms. It’s usually found in coastal vineyards. Due to its texture, this type of soil allows the vine to extend its roots to a considerable depth (6-10 meters), remaining cool and well hydrated. As a result, the wines produced from this type of soil tend to be fresh and light, suitable for biologically aged wines like manzanilla.

– Tosca Cerrada: This albariza is heavier and more compact. It’s known for having a lower number of diatoms. Despite its hardness and compact appearance, it softens and “melts” into smaller pieces when moistened. It’s the most common albariza in the region and the most versatile soil in terms of character and personality, offering full bodied and structured wines. It’s a perfect soil for well-balanced wines that can range from biologically aged styles to extended periods of oxidative aging in the winery. Montegilillo is mostly covered in “tosca cerrada” soil.

– Barajuelas: The lightest subtype of the three, with the highest content of diatoms and calcium carbonate. Its name, “barajuelas,” comes from the Spanish word “baraja,” which is a set of playing cards, usually divided into four suits. The structure of this albariza is arranged in thin layers, thus generating the analogy with a deck of cards. They are exclusively found in the highest areas of the region and typically result in very distinctive wines, with complex structure, suitable for long aging periods.

What grapes are aged on Albariza soil?

If albariza is an unquestionable symbol of the region, so too is the most planted grape variety: palomino. It is a variety particularly resistant to drought and the intense summer heat of the area.

In past centuries, many other grape varieties were used for making Jerez wines, with some being recovered and incorporated into the Designation of Origin (D.O.) today. As in other regions of the world, phylloxera led to a reduction in grape varieties. There are several reasons why Palomino monopolized the vineyards of 20th-century Jerez. However, its perfect symbiosis with albariza soils and its potential for crafting wines destined for aging played a decisive role in the preference for this variety.

Albariza: A Long-Standing Symbol of Quality

The soils, along with the expertise of multiple generations of traders and winemakers, have shaped distinct lines of identity and personality throughout the entire modern and contemporary history of the region. Consequently, albariza has acted as a symbol of quality and excellence throughout the region’s history. With increasing prominence from the 18th century to the present day (due to a deeper understanding of its nature and characteristics), this soil was a part of the selling points for wineries centuries ago. These wineries were pioneers in quality classification and the creation of collections of complex and diverse wines.